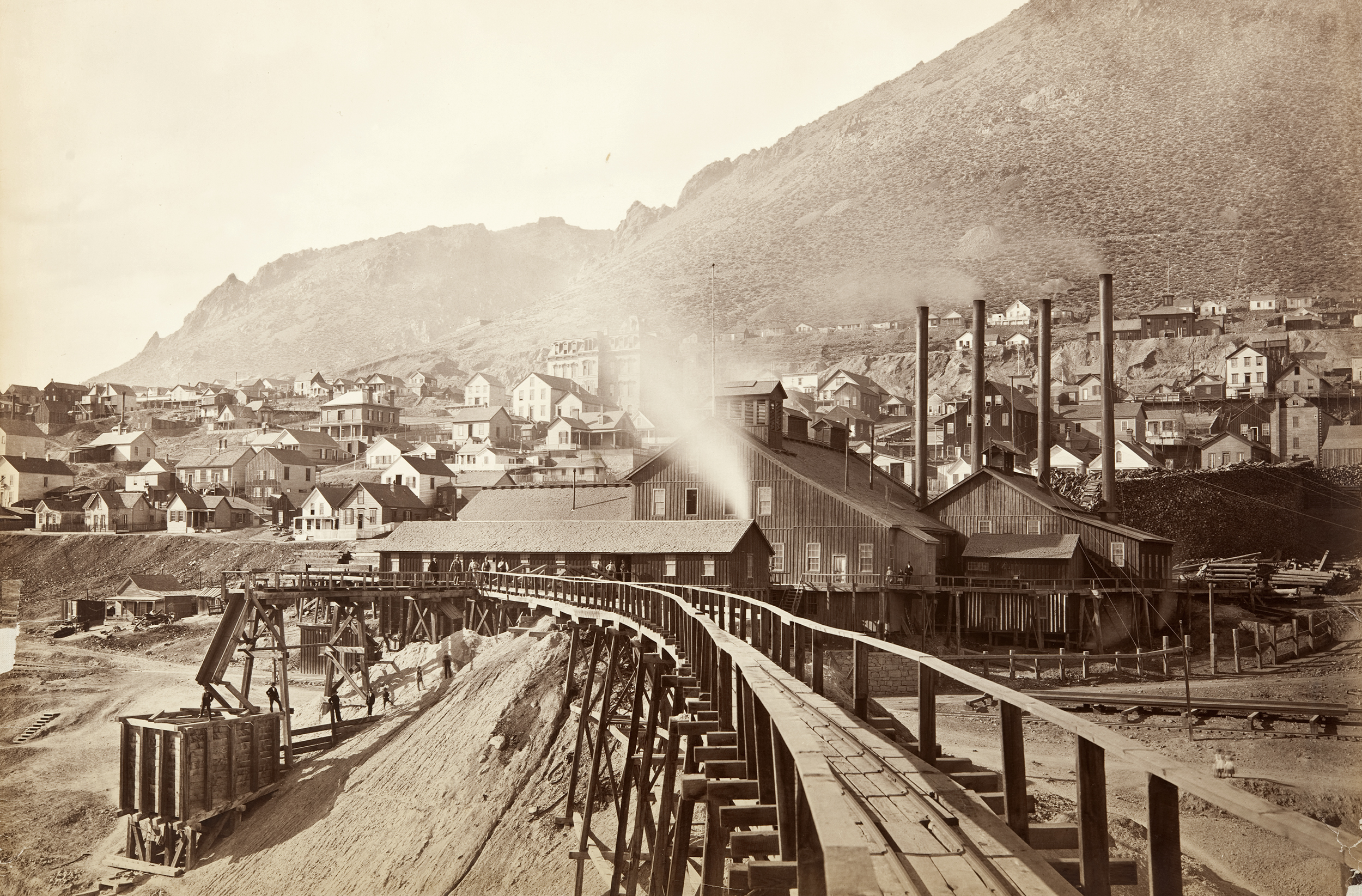

Miners in Virginia City used a Hallidie cable, circa 1867. The innovation helped spawn two familiar modern contraptions. National Archives

When mining camps were the tech incubators of the West

The Gold Rush fizzled in the late 1850s. The California economy sagged into depression. Then, in the spring of 1859, two destitute Irish miners in the mountains east of Lake Tahoe hacked into a layer of crumbly blueish-black rock. The chance find was the apex of the richest vein of gold and silver ore ever discovered in the United States — the legendary Comstock Lode.

The lode was the Silicon Valley of the age — it re-energized California, sparking wild stock market frenzies and driving technological and financial innovation through its 20-year heyday. Today, most people don’t realize that two familiar modern contraptions derive from technology developed to help exploit the Comstock mines.

The Hale & Norcross mine in Virginia City, in present day Nevada, became a thriving commercial center after the discovery of the Comstock Lode.

California State Archives

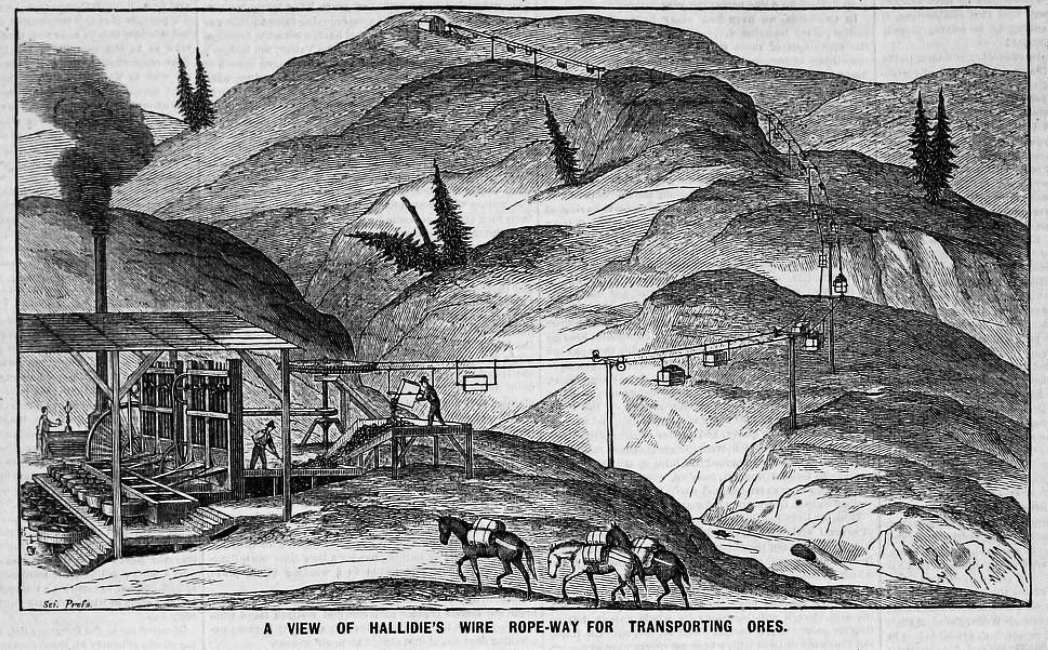

The San Francisco engineer Andrew Smith Hallidie made the best braided wire cables for hoisting ore. He adapted his cables into a device “for the rapid and economical transportation” of ores, lumber, and goods, “over a rough and otherwise inaccessible country.” He called it the “endless-wire rope-way.”

The core of Hallidie’s innovation was a long loop of cable turning at both ends around sturdy wheels and running over rollers held aloft on tall posts. Transport bins dangled from the cable. A steam engine turned the long loop, one side of which climbed with the transport bins to the mine head while the other side descended with them full of ore.

An illustration of Andrew Smith Hallidie’s rope-way from a publication in 1872.

Mining & Scientific Press

Hallidie’s system is the ancestor of the modern ski lift.

Not long after, Hallidie adapted his idea into another invention, this time hiding the traveling cable in a “slot” between a pair of streetcar rails and designing a “grip” that would allow a street car operator to grab on to the cable to move forward and let go to slow or stop. Hallidie’s “novel railroad” was an instant success in San Francisco, where it easily climbed the city’s steep hills, a feat horse-drawn streetcars couldn’t reliably perform. Three old lines operate today, and they’re famous the world over, the universally recognized symbol of San Francisco — the Cable Cars.

Gregory Crouch is the author of the new book “The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West,” just released by Scribner.

The San Francisco Cable Car was derived from mining technology.

Thomas Hawk/CC BY-NC 2.0

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers California’s most compelling news to your inbox each morning — for free. Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.