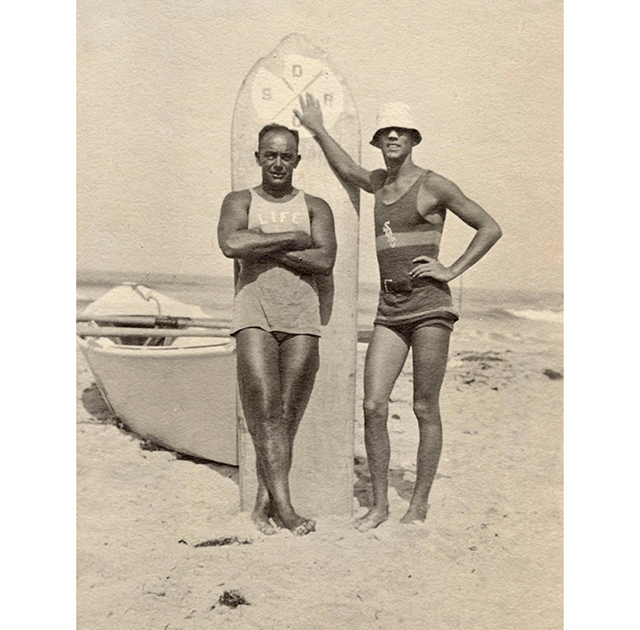

Beachgoers in Long Beach, circa 1910. (California Historical Society)

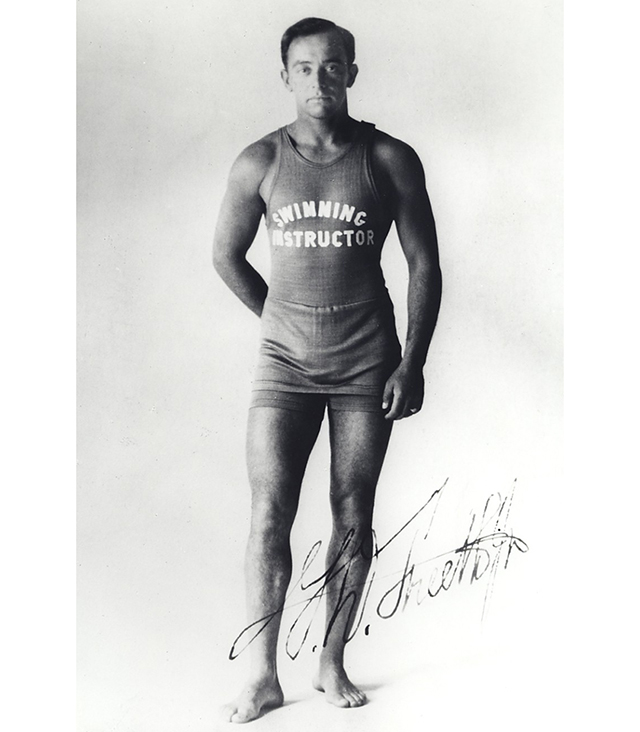

George Freeth, the man who brought surfing to Venice

In the early 1900s, few Californians could swim, let alone surf.

So when a Hawaiian named George Freeth performed surfing demonstrations at Venice Beach in 1907, spectators were mesmerized by the man who could dance on the waves.

Born in 1883 in Waikiki to a Native Hawaiian mother and English father, Freeth fell under the spell of the ocean from a young age.

By the summer of 1907, he was 23 years old and a master of his craft, doing headstands on an 8-foot-long wooden board. That’s when Jack London, vacationing in the islands, became entranced by Freeth and brought him to the world’s attention. In a widely published account, the San Francisco author wrote: “I saw him tearing in on the back of [a wave], standing upright on his board, carelessly poised, a young god with sunburn.”

Later that year, the cigarette magnate Abbot Kinney hired Freeth to perform his “peculiar art” for patrons of his beach resort on the west side of Los Angeles, which he called Venice of America.

Freeth was a surfer king, a champion swimmer, and an expert high diver. Then he became a lifesaving hero.

At the time, many Californians viewed the ocean as a place of mystery and danger. Transplants from the Midwest underestimated rip currents. Women, compelled by modesty, wore Edwardian bathing dresses that became heavy when wet. Drownings were common.

Freeth embarked on a trailblazing career as a beach lifeguard along the Southern California coast. He developed a portable buoy-and-reel rescue device and showed how lifeguards could reach struggling swimmers faster on boards than by boat, as had been the practice. Based on newspaper accounts, the surf historian Patrick Moser wrote, he saved at least 200 people from drowning.

The most celebrated rescue unfolded during a sudden squall in December of 1908, when Freeth was reported to leap from the Venice Pier three times to single-handedly save seven struggling Japanese fishermen. The fishermen were so grateful they changed the name of their village on Santa Monica Bay to Port Freeth.

“History presents no instance of heroism that is greater,” the Los Angeles Herald gushed. “Over and over again he dared the waves and battled with the tempest for human lives.”

Two years later, Freeth was awarded medals for valor by the U.S. Congress and Hawaii.

In 1916, Freeth was recruited to teach swimming in San Diego. In photos from this period, Moser has said, Freeth embodies the quintessential beach culture that would define California: confident, relaxed, fit, tan. It was then, at the height of his strength, that Freeth died. At age 35, he contracted influenza during the tail end of the flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919 and succumbed to lung complications three months later. “In essence,” Moser wrote, “he drowned.”

Freeth’s possessions, according to one account, could fit in the same suitcase he carried when he arrived in Venice 12 years earlier. But he left much else behind: hundreds of saved lives, a modern lifeguard service, and a template for the idea of California itself.

This article is from the California Sun, a newsletter that delivers must-read stories to your inbox each morning . Sign up here.

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.