A cathedral of capitalism on California’s Central Coast

William Randolph Hearst not only ruled over a sprawling media empire. He wielded power as a congressman, a Hollywood heavyweight, and a real estate tycoon whose holdings were so vast that a magazine dubbed him New York City’s “number one realtor.”

Naturally, he needed castle.

If Hearst was among the 20th century’s most powerful men, he was also one of its greatest spenders, said David Nasaw, a biographer of the mogul who took over the San Francisco Examiner in 1887.

“He loved beautiful things,” Nasaw said. “He loved big things. He loved the grandiose. He loved medieval art. He loved the grand architecture of medieval Europe, and believed that he and California deserved a little bit of their own.”

So in 1919, Hearst hired the famed Bay Area architect Julia Morgan to build him a Mediterranean Revival palace on a hilltop facing the Pacific in the Central Coast town of San Simeon.

No expense was spared. La Cuesta Encantada, as it was known, or The Enchanted Hill, included a main residence with 115 rooms surrounded by three villas for guests, each filled with precious artworks. Two pools were added, indoor and outdoor, along with terraced gardens, tennis courts, a movie theater, 41 fireplaces, and a private zoo with giraffes, polar bears, and zebras.

Hearst used the castle as his primary residence, and also as a gathering place for the Hollywood and political elite. Parties were hosted by his movie star companion, Marion Davies, with guests such as Winston Churchill, Charlie Chaplin, Cary Grant, and Greta Garbo.

From left, Charlie Chaplin, George Bernard Shaw, Marion Davies, Louis B. Mayer, and Clark Gable, at the Hearst Castle in 1933.

Ella Strong Denison Library

Work ceased on the castle in 1947, nearly 30 years after it began. Hearst’s company had been diminished by falling newspaper circulation as well as his personal extravagances, which persisted through the Great Depression.

The mogul died a few years later at the age of 88, but his castle would have a second life. The property was handed over to the state of California, and on this week in 1958 it was opened to the public as a historical site. Millions of visitors have since walked its gardens and hallways.

Hearst was a son of Gold Rush San Francisco, a time of myth making about the fortunes to be had with sufficient sweat and savvy. Today, the magnum opus he and Morgan created rises above largely unspoiled coastline as California’s most spectacular monument to capitalism.

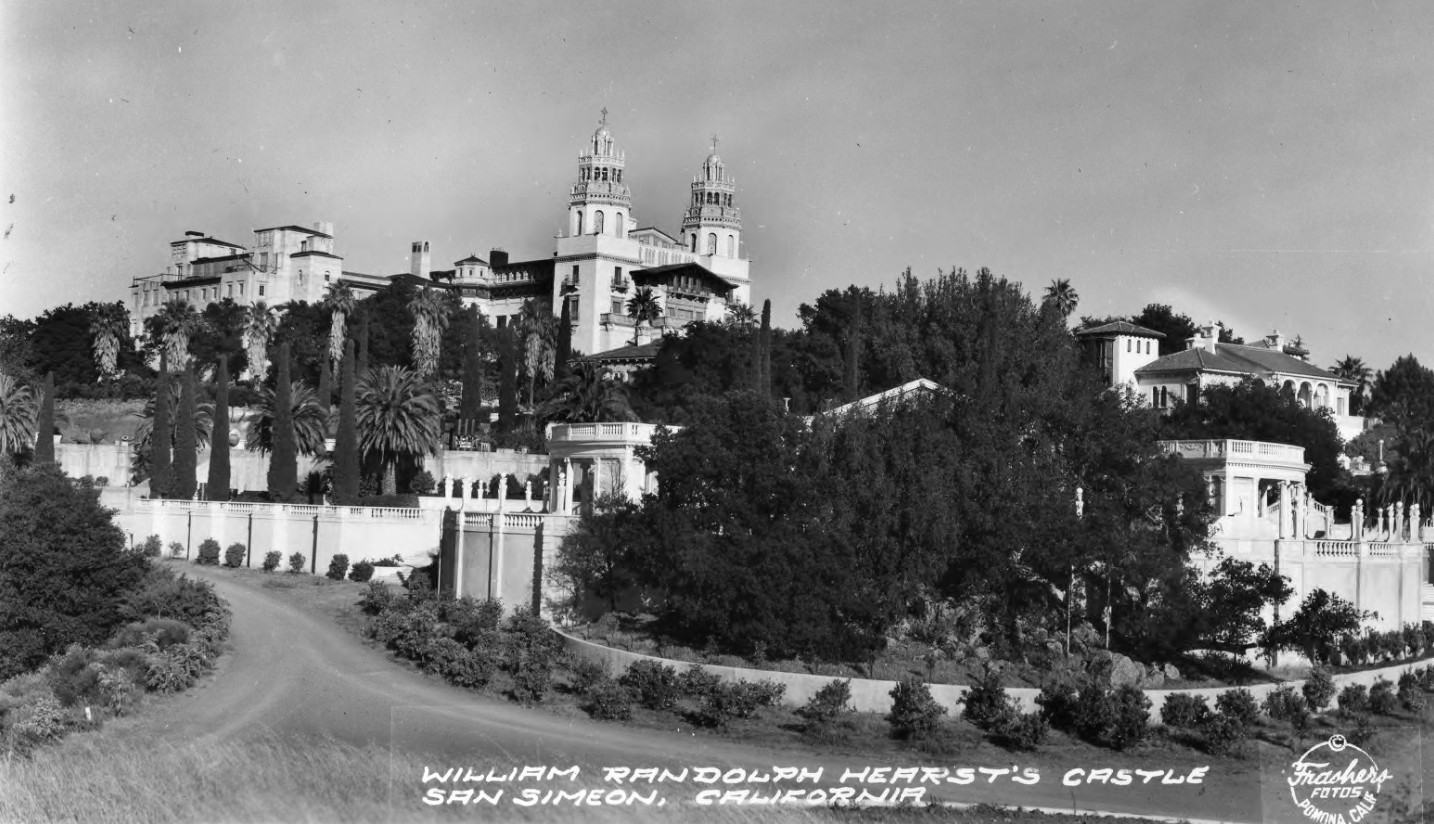

A postcard of Hearst Castle, circa 1975.

California State Library

William Randolph Hearst and his son, George Hearst, at the castle in an undated photo.

Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley

An aerial view of the castle, circa 1931.

H.W. Rudy Truesdale, Kennedy Library, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo

Hearst, circa 1910, was among the most powerful men of the 20th century.

The luxurious Neptune Pool, circa 1939, was a setting for lively parties.

Pomona Public Library

Inside one of the guest houses, circa 1921–1939. The rooms were filled with precious artworks and furniture.

Kennedy Library, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo

A view of Hearst Castle in 1939.

Pomona Public Library

Get your daily dose of the Golden State.